Meeting postponed until further notice.

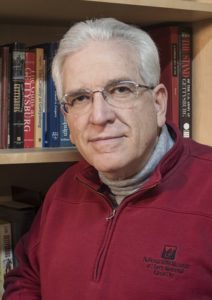

Tom Roza on “American Revolution vs. The Civil War: Similarities and Differences”

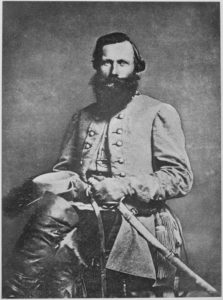

The two most momentous events in the history of the United States of America occurred less than a century apart; the Revolutionary War occurred in 1775-1783 and the Civil War in 1861-1865. An extensive research into the root causes for each of these two conflicts has revealed that there were numerous social, economic, and political similarities—as well as some differences that led to each conflict.

In the 18th Century, because of the vast geographical distance from both England and Europe in general, and the mixing of different ethnic cultures, with each passing day, people living in the Thirteen Colonies were drifting further apart politically, socially, and economically from their European origins. As the 19th Century progressed, the North had become more urban, industrialized, and its citizens were more migrant that produced a philosophy that America was a “Union of States”. Conversely, the South was more rural, agrarian, and its population was more sedentary; generation after generation grew up and lived in the same towns and counties; that produced a philosophy that America was a “Collection of Independent States.”

From a social perspective, for the period leading up to the Revolutionary War, while most of the people living in the thirteen colonies were of English ancestry, cohabitating with other European ethnic groups as well as being in close proximity to Native American Indians produced a vastly different set of values from those living in England and other European countries. Increasingly, the American colonists saw themselves as more independent and were creating a more homogenous society. For the period leading up to the Civil War, American citizens living in the North had retained that homogenous society perspective that resulted in a more inclusive citizenry. American citizens living in the South sociologically had evolved into a more exclusive society that supported slavery and viewed non-Caucasians and those from non-Protestant religions as foreigners.

Tom Roza will discuss the above and more on this interesting subject, which continues to have ramifications for life in these United States to the present day.

Tom Roza has been a student of history for over 60 years. As an officer and the Secretary of the South Bay Civil War Roundtable, Tom has made numerous presentations on the topic of the Civil War to both his Roundtable organization and other historical organizations in the Bay Area. Tom is also a published author of the book entitled, “Windows to the Past: A Virginian’s Experience in the Civil War” that has been accepted by the Library of Congress into its Catalog, and Tom is currently working on a sequel.